Death & Objects II

Neil Goldberg, Emilie Halpern, Ryan Peter, Jasmine Reimer and Major G.L. Thornton Sharp

Curated by: Eric Fredericksen & Jonathan Middleton

The Or Gallery is pleased to announce the opening of Death & Objects II, an exhibition featuring works by Neil Goldberg, Emilie Halpern, Ryan Peter, Jasmine Reimer and Major G.L. Thornton Sharp. The exhibition takes up similar themes as Death & Objects, an exhibition at the Or Gallery that touched on the contemporary memento mori and vanitas, including subtle or abstract anthropomorphisms related to sculpture and the still life.

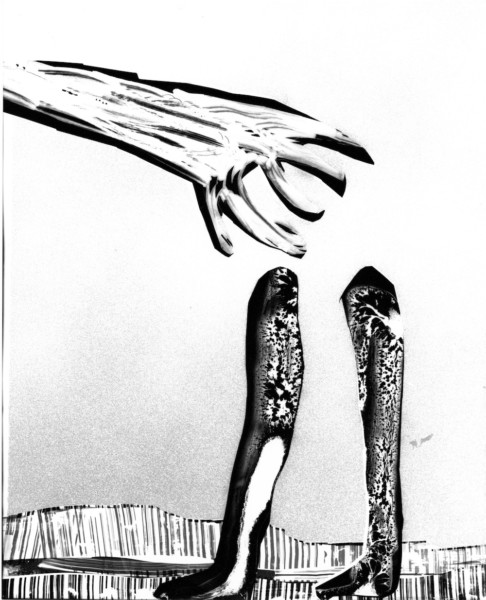

Death & Objects II takes a more direct approach. Works effect a one-to-one relationship in many cases and otherwise address scale and measurement. From Emilie Halpern’s Drown, a puddle of seawater equivalent to the capacity of human lungs, to the sculpture by Jasmine Reimer incorporating casts of cauliflower and the studio floor, the works are indexed to the physical world. Ryan Peter’s photogram series Untitled (AUTOGRAM), portrays what appear to be arms, legs, and other figurative elements against a series of hostile and psychedelic landscapes. While we understand these to be pictures, as with all photograms, they were created by placing objects directly on the photo paper. The title of the series conveys an additional interest in the self-descriptive.

Neil Goldberg’s My Father Breathing Into a Mirror (2005) is what it says. In a one-minute-long looping video, shot in a park with fall leaves, the artist’s father proves, over and over, that he is still breathing. The document’s irony–a proof that is unproven as soon as it is recorded, and thus past–preceded the father’s passing but is deepened by it.

Major G.L. Thornton Sharp’s Victory Square Cenotaph (1924) was erected by public subscription as a monument to Canadian dead of the Great War. Cenotaphs–monuments in the form of a tomb–were erected as war memorials in many Canadian cities in the wake of Edwin Lutyens’ influential 1919 Cenotaph in Whitehall., London. Sharp’s Cenotaph takes the odd form of a truncated obelisk, triangular in plan to suit the shape of the surrounding square. Its inscription, drawn from Lamentations 1:12, is remarkably in-your-face in its address. Walking south across the park from the Or, you read “IS IT NOTHING TO YOV.” If the direct address is not clear enough, the next face clarifies its object: “ALL YE WHO PASS BY.” Finally, the main face, toward Cambie, declares “THEIR NAME LIVETH FOR EVERMORE,” though no names bedeck the monument–a clear difference between it and more contemporary monuments. Its anachronistic insistence on giving death a collective meaning and its retention in collective memory is striking today, while its paradoxical form–not quite cenotaph, not quite obelisk–would have pleased late-20th century postmodern architects. For the purposes of the current exhibition at the Or, we simply underline its transitive function: a monument representing a singular tomb, but standing at the head of no grave, insisting through its formal aspect and its hortatory engravings the reality of mass sacrifice and the necessity of its remembrance.