- Ginger Goodwin Way

- Ginger Goodwin Way

- Ginger Goodwin Way

- Ginger Goodwin Way

Ginger Goodwin Way

27 January–

27 March 2010

Curated by: Jesse Birch

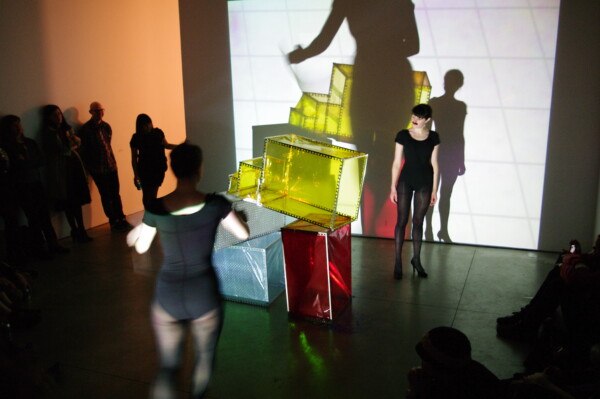

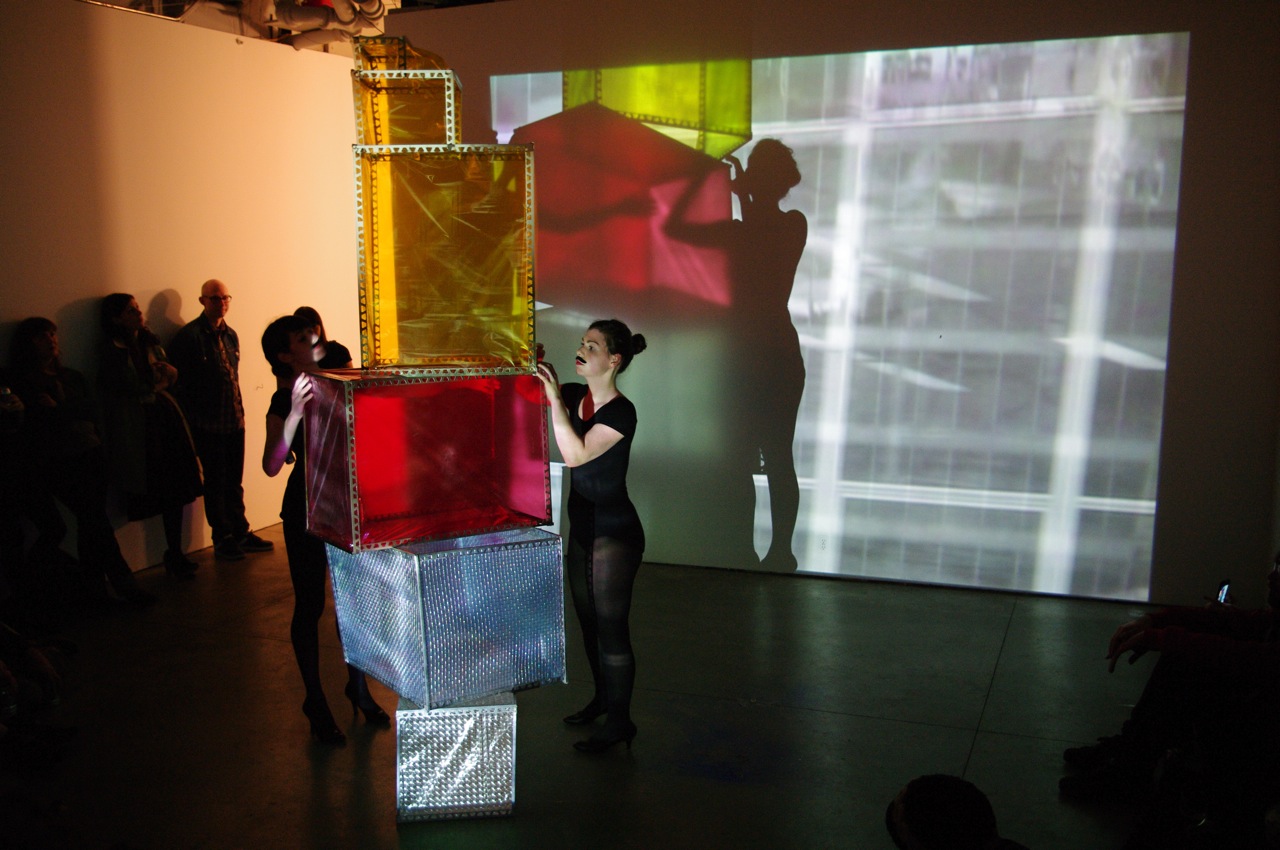

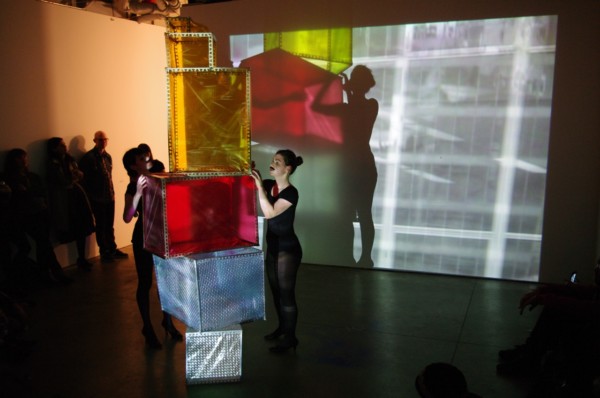

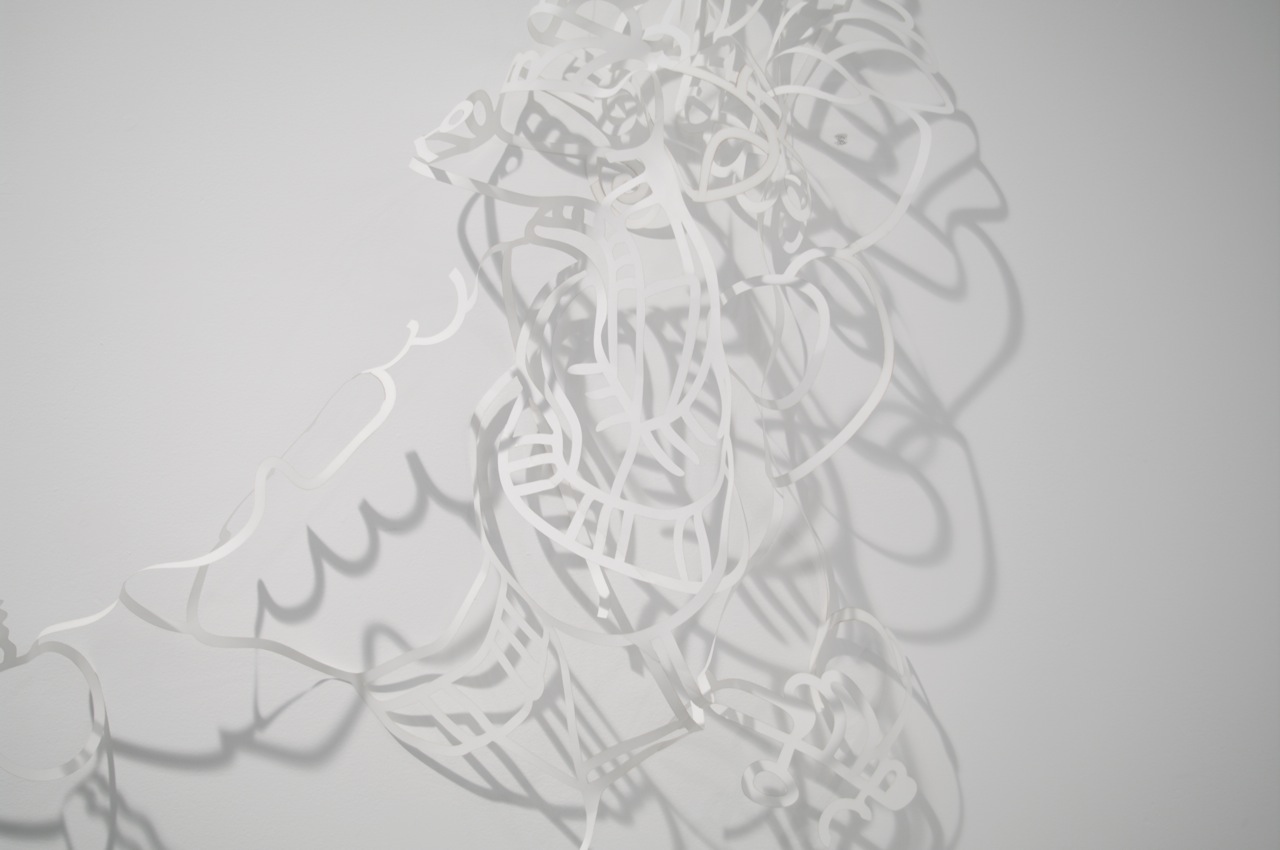

Ginger Goodwin Way, exhibition at Or Gallery, 2010.

Ginger Goodwin Way, exhibition at Or Gallery, 2010.

Ginger Goodwin Way, exhibition at Or Gallery, 2010.

Ginger Goodwin Way, exhibition at Or Gallery, 2010.

Ginger Goodwin Way, exhibition at Or Gallery, 2010.

Ginger Goodwin Way, exhibition at Or Gallery, 2010.

Ginger Goodwin Way

Mariana Castillo Deball, Michele Di Menna, Until We Have A Helicopter

Curated by: Jesse Birch

Ginger Goodwin Way is an exhibition of contemporary art that engages with contested stories and histories: re-interpretations, misinterpretations and unofficial versions.

As one version has it:

In 1918 Albert “Ginger” Goodwin, a miner, and vice president of the British Columbia Federation of Labour, organized a strike that shut down an iron mine and smelter in Trail BC for a number of months. During the strike, even though he was almost blind in one eye, suffered from rotten teeth, stomach ulcers, and bad lungs, he was suddenly conscripted to fight in the First World War. Goodwin fled from Trail to Cumberland BC, on Vancouver Island, where local coalminers helped him hide out with some other draft evaders in a small cabin on Forbidden Plateau. After a few months police Constable Dan Campbell tracked Goodwin down and shot him dead with a soft nose bullet. Campbell, who claimed he fired in self-defense, was never brought to trial. There was a huge funeral procession for Goodwin that filled the streets of Cumberland, and Goodwin’s death resonated in Vancouver, sparking the first general strike in Canada’s history. This synopsis of Goodwinʼs story is one of many, and the facts change depending on where you find it.

I first heard the story of Ginger Goodwin from my aunt, who lives below the Forbidden Plateau in the Comox Valley, but her story focused not only on Ginger Goodwin the man, but also on a sign for a stretch of the Island Highway near Comox named Ginger Goodwin Way. In 1996, to commemorate the fallen miner and to recognize the importance of his story to the history of the region, the provincial New Democratic Party government named a small section of the highway after him. Since it was installed, however, the road sign has generated great debate, and in 2001 the newly appointed provincial Liberals had it quietly removed.

At the time of the removal, B.C. Federation of Labour President Jim Sinclair wrote “Ginger Goodwin was not only an Officer of the Federation, he was a miner, an organizer, a community leader and a tireless advocate for the rights of working people… At least five BC communities have streets commemorating coal baron Robert Dunsmuir. Ginger Goodwin Way provides a very modest balance.”

The story of Ginger Goodwin has always been plural and ambiguous: one figure’s story with many variants. In many ways his story could be seen as a point of contestation between official narratives and those that circulate by other means.

Some local residents protested the removal of Ginger Goodwin Way through an ongoing campaign replacing the sign with makeshift versions: each sign disappeared shortly after it was put in place.

The artists in the exhibition Ginger Goodwin Way take a similar approach by re- interpreting and taking ownership of narratives that are either in danger of being lost, or are only told from one dominant position. The exhibition itself derives from the idea that a story can be told within a story or beside a story without being the only anchor of the particular narrative. Goodwin’s story then, becomes an entry point to approach the diverging stories present in the exhibition itself.