- Camera Florae –Laura Vickerson & Helen Sebelius

- Camera Florae –Laura Vickerson & Helen Sebelius

- Camera Florae –Laura Vickerson & Helen Sebelius

- Camera Florae –Laura Vickerson & Helen Sebelius

Camera Florae

Laura Vickerson & Helen Sebelius

23 April–

21 May 1994

Curated by: Janis Bowley

Laura Vickerson: Camera Florae, 1994. Courtesy of the artist.

Laura Vickerson: Camera Florae, 1994. Courtesy of the artist.

Helen Sebelius: Camera Florae, 1994. Courtesy of the artist.

Laura Vickerson: Camera Florae, 1994. Courtesy of the artist.

Laura Vickerson: Camera Florae, 1994. Courtesy of the artist.

Laura Vickerson: Camera Florae, 1994. Courtesy of the artist.

Helen Sebelius: Camera Florae, 1994. Courtesy of the artist.

Helen Sebelius: Camera Florae, 1994. Courtesy of the artist.

Camera Florae

Laura Vickerson & Helen Sebelius

Curated by: Janis Bowley

Helen Sebelius and Laura Vickerson: Camera Florae

April 23 to May 21 1994

Opening Saturday April 23, 3pm (the artist will be in attendance)

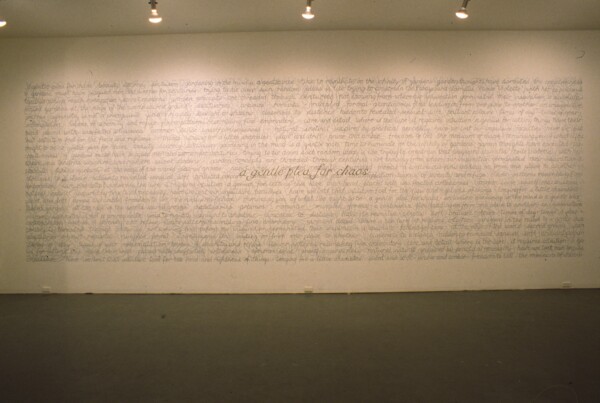

Camera Florae is collaborative installation by Calgary artists Helen Sebilius and Laura Vickerson. Sebelius’ contribution involves the creation of ‘non-objects’ by making images, which are ethereal and transitory, directly on the gallery walls. The artist has written: “the work, comprised of plant and garden images and related text, is made in a way that speaks about the passage of time. Ironically, while the process utilized is labour intensive, the traces left only suggest that a ‘making’ has occurred. The traces are like memories – the work comes near to not existing. The process is a analogy for the nurturing and eventual demise of something of nature.

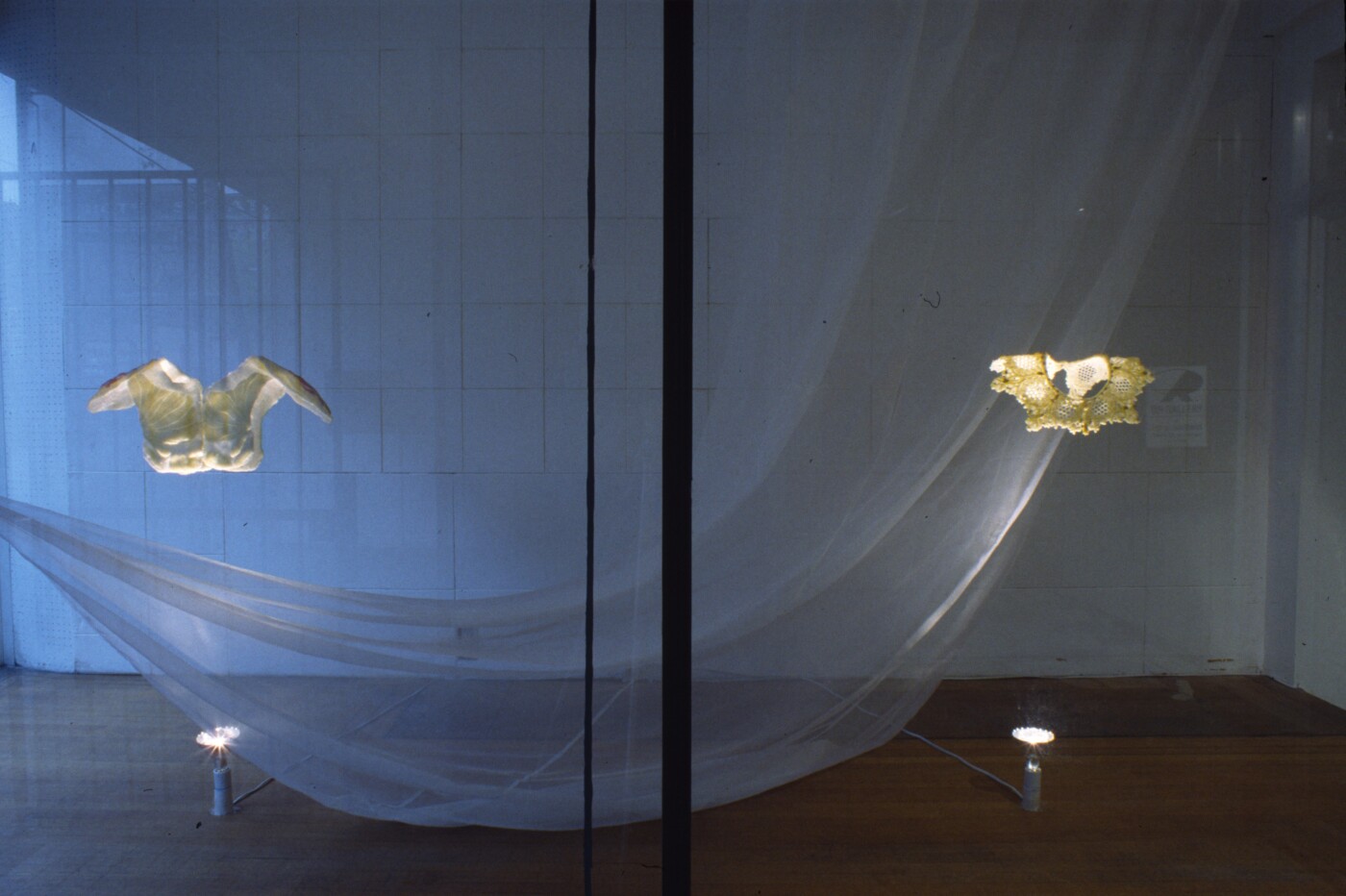

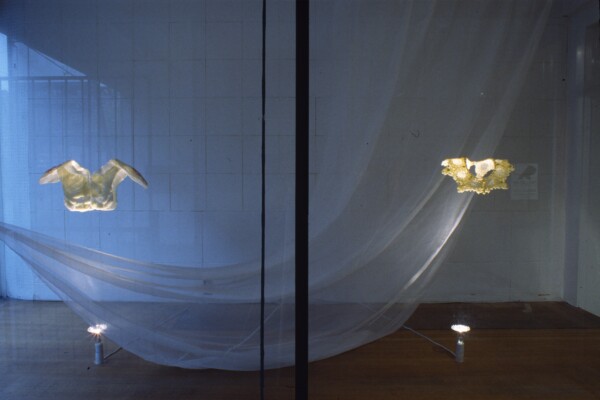

Laura Vickerson is also interested in the transitory quality of the natural world and has created garment like objects using wax forms and plant and flower fragments that elude to the inner workings of the body. The skin-like quality of the wax and red flower petals; like fatty tissue, create a layer of trasnparency acknowledging that these garments neither conceal nor protect. The artist has stated: “The work deals with contradictory qualities of strength and fragility, physical confinement as well as confinement within stereotypes (as in the references to recognizable ‘fashion styles’) and, perhaps most importantly, it speaks about vulnerability.”

essay by Laura Lamb

Laura Vickerson

Ambivalences around ways of looking and discovering, penetration and vision are also central to Laura Vickerson’s work. Vickerson has taken from the garden, not images of plants, but blossoms themselves. She begins by giving the flowers a skin of wax. This preserves them and also transforms them to fleshy things with the shiny density and plumpness of viscera or overripe fruit.

These already meaningful objects (is there anything more culturally loaded than the flower?) become even more heavily burdened with the waxy connotations of morbid wax museums and the sexual activity of bees.

The pins which fasten the blossoms are another material which produce allusions with a remarkable economy. Perhaps their strongest association is to butterfly collections, those cruelly aesthetic objects, which, framed like pictures, ruthlessly exploit a natural decorative beauty commonly thought of as feminine, all the while (to ease the conscience of any morally squeamish aesthete) cloaking themselves in the empiricist authority of entomology.

In the Learning Spanish series Vickerson uses these materials to re-construct pictures of emblematic objects used in language lessons. Her images are reminiscent of the work of Guiseppe Arcimboldo, the Renaissance painter who assembled grotesque and humorous portraits out of pictures of flowers, fruits, vegetables and other objects. Like Arcimboldo, Vickerson’s work combines comic irony with a childlike wonder in the mysteries of representation. The shifts in meaning which take place when one object stands for another while at the same time remaining itself are one of the pleasures of both the modernist practice of collage and of children’s make-believe.

The images used in Learning Spanish (crown, boot, heart, etc.) have been thoroughly stripped of any context to be used as linguistic symbols. Vickerson has then taken from them even their role as teaching aids so that they seem to be nothing but naked signifiers needing a clothing of new meanings. But when the images are reconstructed out of flowers, wax and pins they become so heavily encrusted with connotations that they appear in danger of collapsing under the weight of pleasure. The new pictures are so full of the sweetness and juice of meaning that they seem on the verge of decomposition.

In the Armour Amour series the connotations of both wax and pins shift away from the insects of the garden and towards what the garden has so often stood for – the female body. Wax is utilized for its uncanny resemblance to flesh which so profits Madame Toussaud’s, and the pins while still piercing the blossoms sadistically, refer directly to dressmaking.

Clothing performs cultural functions, both decorating and hiding the body which, unclothed, is supposed to be, like flowers, natural. Vickerson’s work challenges that duality and allows neither cultural artifice nor biological organism to maintain a sense of complacent integrity. Clothing, rather than being a “second skin” here melds with skin and flesh. The costume/body is pierced, slit, and variously opened as if to uncover a hidden interior truth. However each opening up, reveals only an ambivalence between clothing/body, skin/muscle, appearance /reality, artifice/nature.

In Bone Corset the floral pattern on a dress is represented by actual flowers. As the floral decoration becomes literal and three-dimensional, even the decoration on the decoration of the body, the exterior of the exterior, takes on its own corporeality and interiority.

These works, although they are busy with opening up or seeing through the flesh and revealing apparent interiors are more like striptease than autopsy. They tease the viewer by offering a view of an interior which turns out to be no more natural, revealing or truthful than the exterior.

What we encounter when we enter Flora’s Chamber may not be as unrelentingly sweet and pleasant as we expected. If we look closely we find that the Flora’s garden has as much corruption as it has fragrance and that invading the privacy of its mistress risks finding the worms as well as the fruit.

Helen Sebelius — Camera Florae

Today, more than ever we think that we know and love flora. But what of Flora, the feminine personification borrowed from the ancients by two artists and given a room of her own. What will we find on entering Flora’s chamber?

Helen Sebelius’ work revolves around problems of knowledge. In Nascent all drawings recall botanical illustrations, pictures which depict plants not as we usually experience them, in the dirt among the other organisms which give them context and life, but instead attempt to deliver empirical information by presenting each plant as a discrete entity. The plants pictured here have been uprooted and now, upended, are laid out in a neat row. Far from being in a state of being born as the title suggests, they are in a state of dying.

Again in Conjure the earth has been stripped away from the roots, exposing them to the clinical gaze. Like a cadaver in a morgue, the plant is getting the scientific treatment. Hanging over it is the gardening implement which may have done the uprooting. Reminiscent of some archaic surgical device, the tool is an instrument of vision. It aids a kind of looking which sees only what is there, which studies it, analyzes it, produces knowledge by digging up, opening up. How different from the kind of knowledge produced by a vision which is conjured up, the vision which sees only what isn’t there – the imagination.

Between each layer of images and text Sebelius has applied a thin layer of wall paint. The paint forms a skin or a veil, a surface which is important to her work in a number of ways. As a skin the paint represents the very surface of bodily integrity which is threatened by penetrating empirical vision. By drawing our attention to a surface which invites at the same time as it resists penetration Sebelius causes us to become uncomfortably aware of the violations which are part of the production of rational knowledge.

The layer of paint also works as atmospheric perspective (the use of muted colour and haziness to enhance the illusion of distance in traditional landscape painting) to create a space in which a narrative of appearances and apparitions can unfold. At the same time the veil suggests the paradox of imagination. Whatever is there is not quite there.

Like scientists, collagists also remove objects from their contexts. But unlike the data collector, the artist’s interest is not in the object as a singular entity but in the changes in meaning which occur when an element is recontextualized. Sebelius has extracted the text used in A Gentle Plea for Chaos from a book on gardens of the same title. But her extraction is much less severe or radical (of the root) than the surgical act of the botanist. It is an appropriation which seems wholly sympathetic to the artifact she has dismantled.

In the dialogue she has set up between visions, Sebelius answers the rigorous argument of empiricism not with another set of linear propositions, (which might be found in the whole of the text she has appropriated) but with a distillation of the romantic, luscious sensibilities contained in those arguments: an extract of ideas which is presented as a tone.

Sebelius’ work avoids the usual appropriator’s irony which reverses the meaning of a found text. Instead the irony emerges from an ambivalence produced by the coexistence, both in things described and in descriptive methods, of contradictory ways of knowing.