- fictions –Stan Denniston

- fictions –Stan Denniston

- fictions –Stan Denniston

- fictions –Stan Denniston

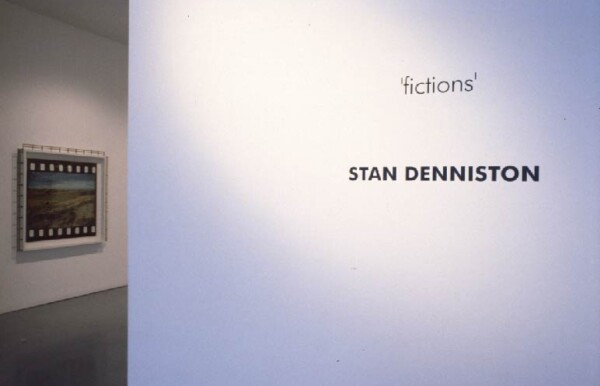

fictions

Stan Denniston

11 February–

11 March 1995

Curated by: Janis Bowley

Stan Denniston, fictions, 1995. Courtesy of the Artist.

fictions

Stan Denniston

Curated by: Janis Bowley

The Or Gallery is pleased to present, to Vancouver audiences, this solo exhibition entitled fictions by Toronto artist Stan Denniston.

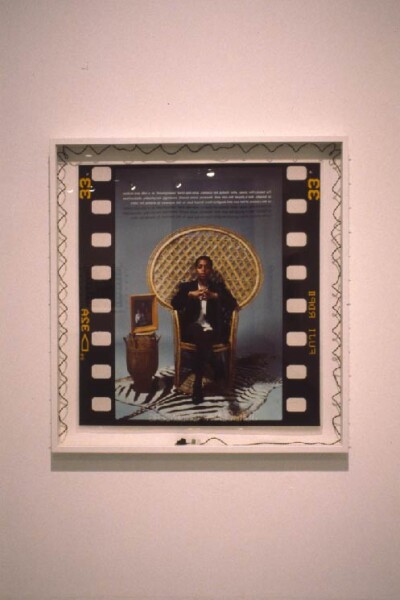

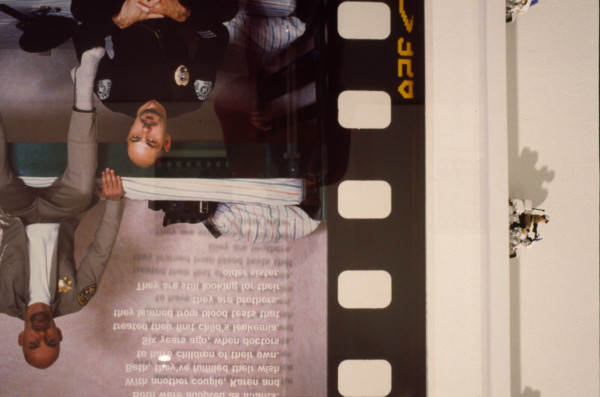

The exhibition consists of new and previously shown colour photographic works of landscapes and portraits. The works are large scale, similar in format, with text and augmented framing devices. Denniston’s work challenges our assumptions of the photograph as a ‘truth-telling’ artifact. The texts which accompany the photographs are descriptive, statistical factual and their proximity to the image conveys credibility. It is the viewer who negotiates the deception. In addition to the disquieting relationship between text and image, Denniston’s work also points to our assumptions of the physical world, particularly the unbuilt environment, with regards to what is ‘natural’ and what is a cultural construct. Both humourous and unsettling, fictions explores the balancing act we often go through when evaluating mediated information.

Stan Denniston once flew to Colorado with his camera, rented a car, and went looking for a military airbase that he was convinced he had read about in The Globe and Mail. He couldn’t find the newspaper clipping before he left and couldn’t find the airbase once he got there. Eventually he concluded that the newspaper story had been part of a dream. Rather than go home empty-handed he found a site that he could photograph as if it were a military airbase – one so well camouflaged you couldn’t see it. The end result was The Natural World (1988-91), Denniston’s first in a series of critical fictions, landscape images overlaid with fictitious texts.

With this exhibition, Denniston introduces a new concept – collaborative portraits or personal fictions. These works, like the mnemonic-representational (Reminders), historical-political (Kent State u., Dealey Plaza), instructional-political (How to Read), and geographical-representational (Colours of Cities) projects, have a seeming truth and truthful seeming that hovers hypnagogically, somewhere between fact and fiction. This meld of documentary and invention also places Denniston’s work within a new Historical Surrealism, an art that is ready to remember, even in an anaesthetized and virtual world.

Denniston’s personal fictions, however, have gone beyond the critical framing of fictional landscape sites. He has taken on the portrait at a time when artists can no longer presume to, or be seen to, define or identify their subject, much less speak for them. Mere acknowledgment or disclosure of bias is not enough to avoid the risk of voice appropriation. Rather than avoid the risk, Denniston’s portraits attempt to push the point back on itself, by encouraging his subjects to re-appropriate, through fiction, their own personal history.

Each of Denniston’s subjects was invited to invent a new or different history for themselves – participating in the construction of the text, staging of the portrait and selection of the final image. With these inter-subjective fictions, Denniston seems to be saying that it is possible and preferable to have a conversation about what might have been, or could have been, or should be, or may yet become, rather than presume to define or contain it.

Within this conversation, the artist is as much reader as author. The privileged authorial perspective is forfeited – but then so, too, are some of the prohibitive strictures that dominate our current discourse on voice and representation.

Denniston’s fiction has gone deep within the artifice of image itself by re-staging the real. My contribution to these fictions (and perhaps my self-portrait) is this: these works are an expression of the desire to break through the increasingly fortified introversion of the Modern Self. As evidence, we cannot help but note that a significant majority of Denniston’s collaborators have offered familial unification themes for their public fictions.

Jeanne Randolph is, for example, ankle deep in her family. She is standing in a total immersion-family-therapy-pool occupied by her husband and son. Michael Fitzgerald and Regan Morris are two gay motorcycle cops who simultaneously discover both their fraternity and their desire for paternity. June Clark-Greenberg is an undercover mother, on the run from a historical past that has now caught up to her children; she must now intervene on their behalf. John Greyson seeks to be out and in at the same time – within the business confraternity of a gay brewers’ association. Jamelie Hassan flirts in the desert of Islamic patriarchy, seeking to pull the rug out from under it through scholarship. And Andrew Lee poses in Hong Kong (a.k.a. Dundas and Spadina in Toronto) with Jennifer Rudder and their son, Tai – except that in this family portrait Andrew is a distracted Hong Kong seed donor reluctantly reunited with the boy and his mother. The stand-in and infertile father is, at the subject’s request, Denniston himself – the camera turned around on the artist, who in this instance is neither author nor progenitor.

These pictures are story circles. The subjects answer the question with a question. But they show more, tell more, and share more, than if they had played it straight or tried to hide. Call it personal history cross-dressing. What better way to resist to the magnetic pull of Identity, the monolith the Moderns once thought to be the source of self?

Adam Phillips has pointed out, the “aim of analysis is to restore the loose ends – and the looser beginnings – to the story… In order to regain interest in the unconscious we have to lose interest in the idea of the superordinate point ofview.”l

Denniston’s new work clearly revels in the “loose ends – and the looser beginnings” (the looser the better) that his subjects have chosen. In Historical Surrealism, personal signifiers freely float within the soup of a social unconscious (a shared space, hot, immediate, like a news-driven internet that we zap into and out of like a lucid dream), rather than a free association of the personal repressed (a private, insular space, where the self holds all the cards and is known to frequently deal from the bottom of the deck.). The Jungian model of a deeply buried archive of time-worn archetypes is nowhere in sight.

It is possible now only because of the end of the cold war between Realism and Surrealism. Realism imposed the “literary” 2 which Greenberg feared would kill painting, and reinforced a dependency on what Barthes called “perfidious Analogy” 3. Surrealism became (after Breton) subsumed by and within a detached, abstract avant garde, more samizdat than modern. But now the wall between the photograph as evidence and the photograph as representation has been demolished. Denniston has been to that wall and back again, the euphoria and celebratory jouissance have long since waned, and a new pragmatics has set in to take their place.

Denniston’s portraits suggest, in light of the looser set of beginnings these fictions expose, that there may be a way of restarting our conversations, conversations that have been of late prohibited, impossible or incorrect – about desire, about origins, about perceptions. We should not believe everything we dream in the newspapers, but nor should we be suprised if some of it holds true.

Russell Keziere

1. Adam Phillips, On Kissing, Tickling and Being Bored (Psychoanalytic Essays on the Unexamined Life) (Harvard, 1994), p. 7.

2. In 1940 Greenberg wrote about 18th century Romantic Revival painting in Towards a New Laocoon: “It was not realistic imitation in itself that did the damage so much as realistic illusion in the service of sentimental and declamatory literature.” The Collected EssO)is and Criticism, Volume 1, (University of Chicago Press) p. 27.

3. “Analogy implies an effect of Nature: it constitutes the “natural as a source of truth; and what adds to the curse of analogy is the fact that it is irrepressible: no sooner is a form seen than it must resemble something; humanity seems doomed to Analogy, i.e., in the long run, to Nature.n Roland Barthes by Roland Banhes, (University of California Press, 1994, trans. Richard Howard), p.44

fictions - Stan Denniston (1,020.68 KB)